The relationship between the houses

We are creating in these two chambers … what you may term an irresistible force on the one side, and what may prove to be an immovable object on the other side.

Alfred Deakin, Australasian Federal Convention, Sydney, 1897

The use of traditional British forms and symbols in the new Australian Parliament tended to disguise the fact that this was a new and untried institution. It differed radically from the British and colonial parliaments in that legislative power was shared equally between two democratically elected houses—the Senate and the House of Representatives.

The founders of our constitution anticipated that the two powerful democratically elected houses that they had created would sometimes come into conflict. The first significant test of wills between the Senate and the House of Representatives came in the second month of the new Parliament. The House of Representatives passed a bill to supply the government with the money needed to pay the salaries of parliamentarians, public servants and the expenses of the new federal government. The bill contained only the gross amount to be appropriated, and no figures upon which the Senate could exercise its judgment. The Senate refused to sign such a blank cheque and requested the House to provide details explaining the purposes for which the money was to be used.

The House withdrew the bill and introduced Supply Bill No 2, to which was attached a schedule giving these details. The wording of the new Bill implied that the act of granting the supply of money to the government was made by the House only and that the Senate played no role in the process. The Senate rejected this interpretation of the Constitution and requested that the wording be amended to make it clear that money was provided to the government only with the approval of the whole Parliament. The House made the amendments requested by the Senate.

The second major occasion when the relationship between the houses was tested occurred in 1902 when the Senate insisted on changes to the Customs Tariff Bill. As this was a bill which proposed the imposition of taxation, under section 53 of the Constitution the Senate could not amend it, but it could request the House to make amendments.

The Senate made 93 requests for the House to make amendments. The House agreed to make some of these amendments but refused to make others. When the Senate then insisted on, or ‘pressed’, its requests some members of the House of Representatives claimed that this was unconstitutional. Other members of the House argued that the Senate was within its rights to continue to press its requests. After much debate the House resolved that because of the urgent need to pass the bill it would refrain from ‘the determination of its constitutional rights’ on this matter. Both houses finally agreed on the provisions of the bill and the principle that the Senate could press its requests was established.

… we are creating a senate which will feel the sap of popular election in its veins, that senate will probably feel stronger than a senate or upper chamber which is elected only on a partial franchise

Dr John Quick, Australasian Federal Convention, Sydney, 1897

THE FIRST CLOUD. THE SENATE (Col. Neild). — 'I tell you I won't consent to the paying of your Bills if you do not supply items.'

REPRESENTATIVE (Mr. Barton) — 'Here's a nice squalid squabble—just as we'd set up House-keeping, too. I suppose I must obey, but you show very little confidence in me.' |

Sir William Orchardson’s painting ‘The First Cloud’ (1887), depicting a newly-wed couple’s first tiff, had been purchased by the National Gallery of Victoria and would have been familiar to many Melburnians. The cartoonist has cleverly adapted the painting to mark the appearance of ‘The First Cloud’ over relations between the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Senate had objected to the lack of an itemised list of expenditure in the first Supply Bill. Here Prime Minister Barton is depicted as the young wife and Senator Nield as the husband. |

| Punch (Melbourne) 20 June 1901 |

Rules, conventions and symbols

|

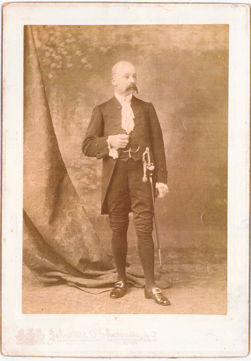

George Upward, first Usher of the Black Rod in the Senate

Bulletin (Sydney), 18 May 1901 |

Each house of Parliament had the power derived from the Constitution to make standing orders to govern the conduct of its proceedings. Until the chambers adopted their own rules, the presiding officers used generally accepted parliamentary principles and common sense to guide them in the conduct of business.

In June 1901 the House of Representatives adopted standing orders drafted by the clerks of both houses and these continued to operate in the House until 1950. The Senate rejected a similar set of orders and used the procedural rules of the South Australian House of Assembly until a set of standing orders devised by the Senate Standing Orders Committee was accepted by the Senate and came into force on 1 September 1903.

|

Many of the symbols, conventions and ceremonies used in the new Australian Parliament were drawn from the British parliamentary tradition, either directly, or through the members’ or clerks’ experience in colonial parliaments. These traditions included:

- Titles of parliamentary officers, their symbols of office and their form of dress.

- Rules governing progress of legislation through the chambers, formalised in standing orders, and providing for three ‘reading’ stages, and referral for royal assent.

- The convention that the monarch or her representative should not enter the lower house. The Governor-General therefore addressed the parliament in the Senate chamber.

- Rules of behaviour in the chambers, encompassing ideas of acceptable dress, language and address

|

Thomas Woollard, first Serjeant-at-Arms of the House of Representatives

With the permission of Mrs Moira McLean |

|