Drafting A Constitution

the draft of 1891 is the Constitution of 1900, not its father or grandfather.

A meeting of representatives of each of the Australian colonies and New Zealand, called the National Australasian Convention, was held in Sydney from 2 March to 9 April 1891.

The delegates worked to find a draft constitution to which they could agree and which they could take back to their parliaments for discussion and endorsement.

Andrew Inglis Clark

National Library of Australia

A Tasmanian lawyer, Andrew Inglis Clark, had circulated a draft constitution to many of the delegates before the Convention began. A Constitutional Committee, under Sir Samuel Griffith, adapted Clark's draft and produced the copy which, in essence, received the final endorsement of the Convention as the Australian Constitution Bill of 1891.

Later conferences and conventions amended some aspects of the Australian Constitution Bill of 1891. In substance, however, the Australian Constitution was drafted at the 1891 Convention.

|

|

Annotated Constitution Bill, National Australian Convention, 1891

Barton Papers, National Library of Australia

Delegates to the 1891 Convention worked on printed draft constitutions that derived largely from a version circulated by Inglis Clark. Here Barton has pencilled in amendments relating to the office of Governor-General. |

|

Lucinda (ship) ca. 1897

Unknown Artist

State Library of Queensland

The Premier of Queensland, Sir Samuel Griffith, had travelled to Sydney on the Queensland government steamship Lucinda to participate in the federation Convention. During the Easter weekend of 27/29 March 1891, Griffith made a cruise in the Lucinda to the estuary of the Hawkesbury River, taking with him Kingston and Barton, and picking up Inglis Clark on the Sunday. During the cruise, this drafting sub-committee finalised the draft of the 1891 Constitution.

Through its association with the Australian Constitution, the Lucinda has become a symbol of Australian democracy. |

The Australasian Federal Convention, held in three sessions in 1897 and 1898, was made up of ten delegates from each of the Australian colonies except Queensland. The delegates to this Convention, who were popularly elected and could thus claim legitimately to speak for the Australian people, debated the bill clause by clause and made some significant amendments. Further amendments were made at a premiers' conference in January and February 1899, and in response to requests for minor amendments by the House of Commons in May 1900.

|

The Australasian Federation Convention meeting in the chamber of the South Australian House of Assembly in Adelaide in 1897

National Library of Australia |

Where did the ideas come from?

Australian colonists enjoyed the individual and civil rights of British subjects and were governed by British law. They aspired to govern themselves according to the British tradition of parliamentary democracy. A democratic temper prevailed in Australia and as each colony was granted self-government the right to vote was extended to a wider proportion of the population.

|

The First Parliamentary Election, Bendigo, 1855,

by Theodore King, oil on canvas (31.5 x 45.5cm)

Bendigo Art Gallery. Gift of Mr JS Dethridge, 1894.

The painting depicts a meeting of miners in front of the Criterion Hotel in Bendigo in 1855, to endorse the nomination of Dr John Owens as representative for the goldfields in the Victorian Legislative Council. As such, Owens represented more than half the population of Victoria. |

The delegates to the conventions at which the Constitution was drafted were almost without exception members or former members of colonial legislatures. They were able to draw on many years of combined experience in the working of colonial constitutions to assist them in devising a parliament to suit the needs of an Australian Federation. The colonial parliaments provided the delegates with examples of what was workable in a parliament, and what should be avoided.

|

Australia kneels before Queen Victoria, who has granted nationhood

H. Cotton, ink and wash drawing

National Library of Australia |

In each of the colonies the constitution had been modelled on the British system of responsible government and the monarchy was therefore an integral part of it. In this system executive power, nominally held by a Governor representing the monarch, was in practice exercised by ministers who were members of parliament, and who continued in office only so long as they had the support of a majority of the lower house.

The members of the colonial parliaments were used to working in the context of the British monarchy and saw no incongruity in aspiring to independence under the Crown. Although there were some Australians in favour of a republican model of government for the new Federation, the overwhelming majority of delegates favoured a variant of the system they were familiar with.

The delegates examined the example of Canada, where a federation under the Crown already existed, with a parliament of two houses, one elected on a population basis and the other, representing the provinces, to which members were appointed rather than elected. While some elements of the Canadian constitution were adopted, the Canadian form of federalism, where residual powers rest with the federal government rather than the provinces, was felt to be too centralised for the Australian situation.

The American system of government was also frequently referred to in debate. The United States Congress, in which a lower house elected on a population basis, and an upper house representing the states equally, exercise almost equal legislative powers, provided an example of a successful federal legislature. The division in the Australian Constitution of the government into legislative, executive and judicial branches is a clear reference to the doctrine of the separation of powers which helped shape the American constitution.

The constitutions of a number of other countries were also considered at the constitutional conventions, including those of Switzerland, Germany, and South Africa.

|

‘Towards This’

Punch (Melbourne), 2 June 1898

National Library of Australia

Elements of the form of government

chosen for Australia were borrowed

from that of other countries—principally

the United Kingdom (represented by

the lion) and the United States (the eagle).

Other features are uniquely Australian (the kangaroo) |

What were the major arguments at the conventions?

A major topic for debate at the federal conventions was how to achieve a balance between the representation in the federal parliament of the interests of people of the populous states of New South Wales and Victoria, who would have a majority of seats in a legislature elected on a population basis, and those of people in the states with relatively small populations. It was widely held as a tenet of democracy that the power of the purse should lie with a chamber elected on the basis of population, and not with a body in which communities were represented equally, without regard to population.

The solution which emerged was a parliament of two houses: one, the House of Representatives, consisting of members representing approximately equal numbers of people, and the other, the Senate, consisting of an equal number of members elected from each state. The assent of both houses would be needed to pass laws. The Senate, elected by the same people as the House of Representatives but voting in states, provided the compromise which was necessary for the smaller colonies to agree to join the federation. On the question of financial legislation, the smaller colonies compromised, and allowed a qualification in the Senate's power over money bills.

|

Relative voting power of the individual in the Senate under federation

Federation-Australia Album MS 5911/94, National Library of Australia

As it takes many fewer votes to elect a senator in a small state

than a large one, the voting power of the individual is much

greater in Western Australia than in, say, New South Wales. |

– From "Federation," by Messrs, Hughes and Dick, Ms. P.

The Constitution Bill rings the death-knell of majority rule. The diagram herewith shows (by height of figures) the relative voting strength of the several States for the Federal Senate. One Tasmanian has eight times the voting power of one New South Wales man. Forty-one per cent of the people of the federating States reside in New South Wales. In the course of a few years she will probably contain more than half the population, and contribute at least half the taxation.

In the Federal Senate, New South Wales is given, and will for ever have, only one-fifth of the voting strength. The "Yes" to the Bill means a final verdict – "No," a temporary remand. It is not a question of "Federation now or never." It is "the Convention Bill now (and for ever), or a better Bill later on " – with Queensland included.

|

There was general agreement as to the scope of the new parliament’s legislative powers. The law-making powers defined for the federal parliament included those areas which had long been recognised as the logical responsibility of a central government—matters such as trade and commerce, defence, and immigration. Some powers were defined as exclusive powers of the federal parliament, and some were to be concurrent with the powers of the state parliaments. Many issues were decided provisionally, ‘until the parliament otherwise decides’.

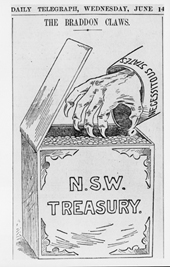

Under section 87 of the Constitution, the ‘Braddon clause’, three-quarters of all revenue acquired by the Commonwealth through customs and excise was to be returned to the states, for a period of ten years after Federation. Some feared that this would result in the more populous states subsidising those with small populations. |

The Braddon Claws

Daily Telegraph (Sydney), 14 June 1899

National Library of Australia |

Approving the Constitution

Referendums on the proposed Federal Constitution Bill were submitted to Australian people in 1898 and 1899. In all cases the majority of voters in each of the colonies voted in favour of the Bill.

How Australia Voted

Results of the referendums held on the Draft Bill to

Constitute the Commonwealth of Australia

| |

New South Wales |

Victoria |

South Australia |

Tasmania |

Total |

For |

71,595 |

100,520 |

35,800 |

11,797 |

219,712 |

Against |

66,228 |

22,099 |

17,320 |

2,716 |

108,363 |

Majority |

5,367 |

78,421 |

18,480 |

9,081 |

111,349 |

(Quick and Garran, p.213)

| |

New South Wales

|

Victoria

|

South Australia

|

Tasmania

|

Queensland

|

Total |

| |

20 June |

27 July |

29 April |

27 July |

2 September |

|

For |

107,420 |

152,653 |

65,990 |

13,437 |

38,488 |

377,988 |

Against |

82,741 |

9,805 |

17,053 |

791 |

30,996 |

141,386 |

Majority |

24,679 |

142,848 |

49,937 |

12,646 |

7,492 |

236,602 |

(Quick and Garran, p.225)

WESTERN AUSTRALIA - 31 July 1900 |

| |

For |

Against |

Majority |

Metropolitan Electorates

Fremantle Electorates

Goldfields Electorates

Country Electorates |

7,008

4,687

26,330

6,775 |

4,380

3,141

1,813

10,357 |

2,628

1,546

24,517

-3,582 |

Total |

44,800 |

19,691 |

25,109 |

(Quick and Garran, p.250)

|

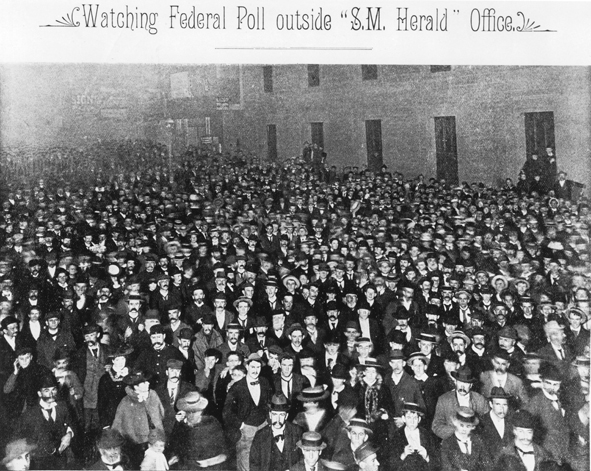

Watching the federal poll outside the Sydney Morning Herald Office. From the book Souvenir of the inauguration of the Australian Commonwealth

National Library of Australia |

The final bill

I welcome it as the most magnificent constitution into which the chosen representatives of a free and enlightened people have ever breathed the life of popular sentiment and national hope .

Charles Cameron Kingston, Constitutional Convention, Melbourne 17 March 1898.

The draft Constitution, as endorsed by the Australian people, needed the approval of the British Parliament. The Commonwealth of Australian Constitution Act was passed by the British Parliament and received the assent of Queen Victoria on 9 July 1900. It came into effect on 1 January 1901.

While parts of the Australian Constitution were clearly patterned on the constitutions of other countries and colonies, the final result was a unique and original system of government. The Australian founding fathers mixed their precedents carefully and creatively, and added many novel elements.

The constitution was written, in its final stages, by popularly elected delegates, and endorsed by the people of Australia twice at referendum.

The parliamentary model chosen for and by the Australian people, with its provision for two popularly-elected houses, recourse to referendum for constitutional amendment, and referral to the people of disagreements between the houses, was one of the most democratic in the world when it was adopted. It remains so after the passage of more than one hundred years.

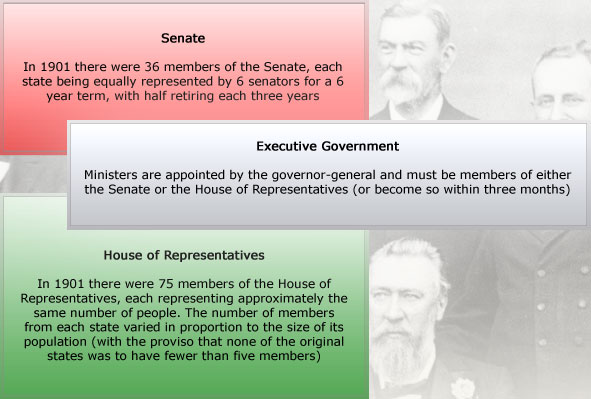

The powers and composition of Parliament

The new Australian Constitution provided for two elected houses of the Commonwealth Parliament—the Senate and the House of Representatives.

- The Senate was to consist of 36 members, 6 from each state

- The House of Representatives was to have approximately twice as many members as the Senate

- Both houses were to be elected directly by the people

- All proposed laws (bills) were to be passed by both houses to become law

- The powers of both houses of Parliament were to be the same

—except that the Senate could not introduce or amend certain money bills. The Senate could, however, request that the House of Representatives make amendments to such bills and had the power to refuse to pass any bill

- The Constitution provided a method for resolving deadlocks between the two houses over proposed laws

—Under certain conditions specified in the Constitution both houses could be simultaneously dissolved, in which case elections would be for all seats in both houses. If the deadlock persisted after the elections the Governor-General could convene a joint sitting of the two houses to resolve the matter.

- The Parliament was empowered to make laws for the ‘peace order and good government of the Commonwealth’ in relation to matters specified in the Constitution

—These powers included defence, invalid and old-age pensions, marriage and divorce, currency, immigration, tariffs, taxation, and certain aspects of banking and commerce

- The Constitution gave the Parliament the powers necessary to conduct its affairs and to protect its integrity

- Members of the executive government (ministers) were to be appointed from among the members of Parliament by the monarch’s representative, the Governor-General.

The Australian colonies had adopted the British tradition that government ministers were appointed by the monarch on the advice of the leader of the party or coalition with a majority in the lower house of parliament. This practice was so widely understood and accepted that it was not written into the Australian Constitution. The British monarch is legally a part of the Parliament: section 1 of the Constitution provides that the Parliament ‘shall consist of the Queen, a Senate and a House of Representatives’.

|